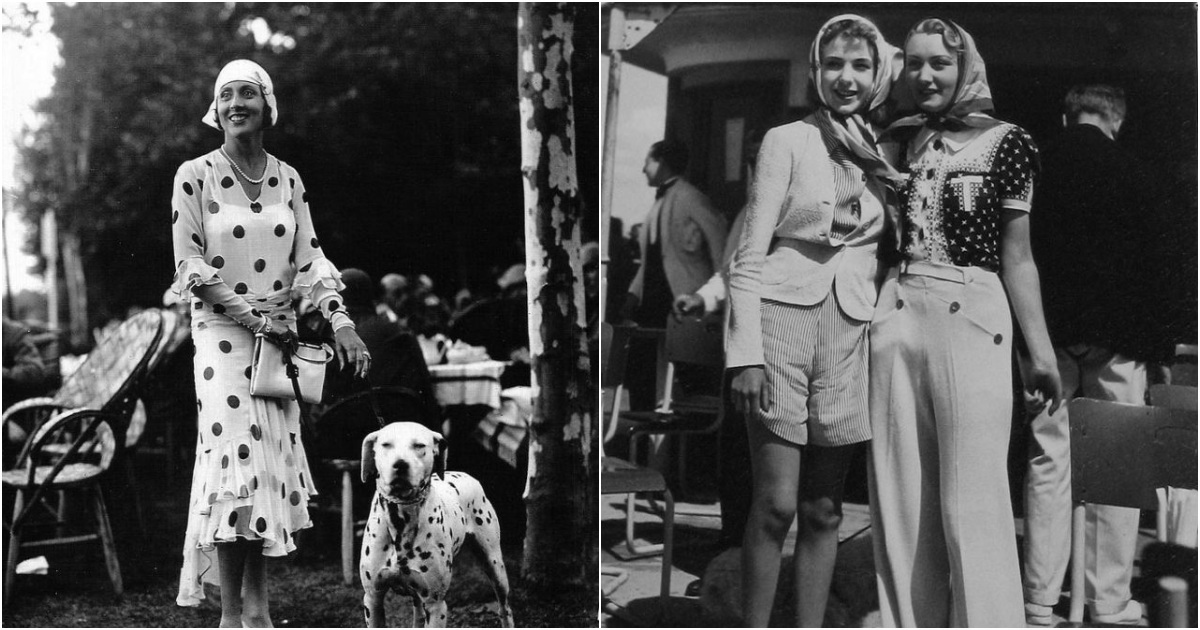

Passing round the product at an outdoor Tupperware. Hosts had a strict dress code – skirts and stockings were mandatory. 1955.

When an amateur inventor and designer named Earl Silas Tupper first invented Tupperware around 1942 (from a refined version of polyethylene that he referred to as “Poly-T: Material of the Future), he envisaged the total “Tupperization” of the American home.

Throughout the Depression Tupper had persevered in his endeavor to become a commercial inventor and transform his economically precarious life from rags to riches.

Women’s lives, he believed, would be considerably enhanced by his new labor-saving, flexible, lightweight containers; no more spills and odors in the refrigerator, no more waste leftovers.

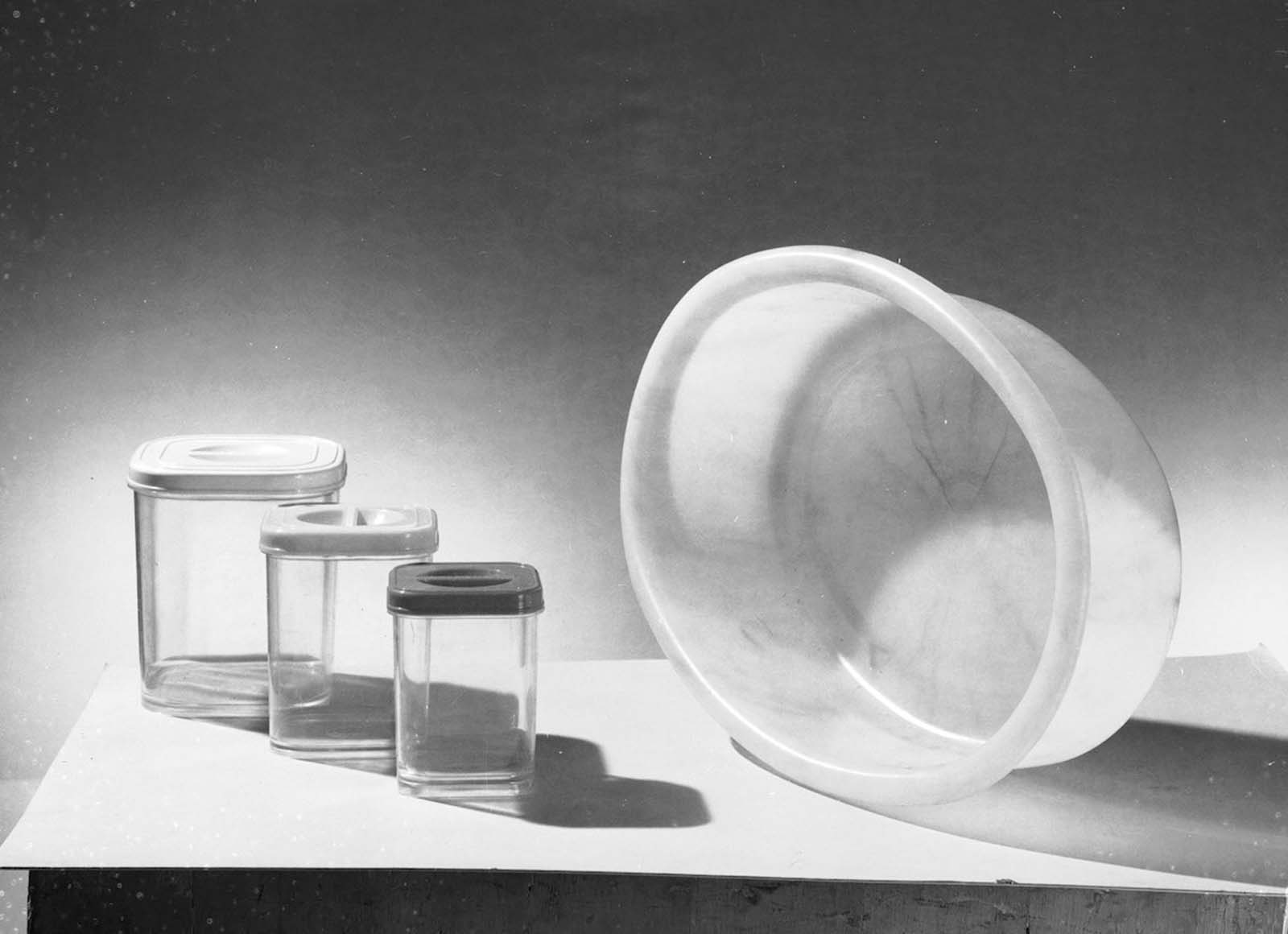

By 1947, home magazines such as House Beautiful hailed Tupperware designs as “Fine Art for 39 Cents” with gorgeous textures reminiscent of jade and mother-of-pearl, but American housewives remained largely unimpressed.

Department store displays and newspaper advertisements promoted Tupperware as the answer to the dreams of the modern homemaker, but still, the sales dwindled.

A Tupperware party in full swing. A table in the foreground displays a range of the company’s products. 1950s.

Then in the early 1950s, Brownie Wise, a middle-aged housewife and impoverished single mother living in Detroit initiated the Tupperware party.

Wise had sold Tupperware as an independent door-to-door salesperson to pay her young son’s medical bills and Earl Tupper, astonished by her sales figures, demanded to know her secret; it was, she responded, “The Tupperware party.” By 1951, convinced by the success of direct selling, Tupper agreed to withdraw Tupperware products from all department stores and retail outlets.

The Tupperware party became the company’s exclusive form of distribution. Wise was awarded the position of the vice president leading the newly formed Tupperware Home Parties Incorporated (THP).

She began her amazing transition from housewife to leader of a multimillion-dollar enterprise, appearing in women’s magazines and business journals across the land.

Women attend a Tupperware party, hosted to market the new brand of plastic containers. 1955.

By the mid-1950s, the Tupperware party (at which women gathered in the home of the volunteering “hostess” to lively product demonstration) had become a cultural hallmark of postwar America.

While Earl Tupper continued to expand his product range, inventing cocktail shakers and hors d’oeuvre dishes for a newly affluent population, Brownie Wise recruited Tupperware dealers in droves.

In 1954, she became the first woman to grace the front cover of Business Week with her adage, “If we build the people, they’ll build the business.”

The accompanying editorial described her quirky and outlandish sales and recruitment techniques. Poly, a piece of black polyethylene slag insured for $50,00, accompanied her on nationwide trips to dealer and distributor sales rallies.

As the inspiration behind Earl Tupper’s first injection-molded Tupperware tumbler, the molten lump became a potent Tupperware talisman: “I tell [dealers],” Wise informed Business Week, “to shut their eyes, rub their hands on Poly, wish, and work like the devil, then they’re bound to succeed.”

Despite the astounding success of the Tupperware enterprise, which received constant press coverage and design and business accolades, Tupper and Wise held widely differing approaches to the business.

Tupper despised large gatherings of people and refused to attend the annual sales rallies known as Homecoming Jubilees, but Wise reigned over her Tupperware dealers with increasingly flamboyant displays of charisma.

A suitably attired woman attends a Tupperware party. 1955.

While Tupper led the design development of ketchup funnels and cake domes at the Tupper Corporation factories in Massachusetts, Wise gave away items from her personal wardrobe, lavish evening dresses, coordinating hats and accessories, to her sales elite (the “Vanguard”) in Orlando. At the height of Tupperware’s success in the 1950s, Tupper furnished his home in the restrained style of traditional New England good taste.

Wise’s Florida home, filled with contemporary artwork, rattan furniture, and flamingo pink upholstery, was described by one journalist as being more like “the lobby of a swank beach hotel.”

On the one hand, Tupperware taught thrift and containment; on the other, excess and abundance. These contradictions were indicative not merely of biographical and gender differences, but of the historical shift from the Depression economy to the postwar boom.

The Tupperware party, a phenomenon less easily explained by theories of utilitarianism, originated according to corporate anecdote as an expedient way of showing bewildered 1950s housewives how to fit the Tupperware seal securely on their polyethylene containers.

A woman browses the catalogue at a Tupperware party. 1955.

The notion of “bewildered” housewives, ambling the bridge party to Tupperware party, compounds the notion of the all-consuming postwar American woman, capable of accomplishing little more than attending coffee hours, shopping (under the influence of corporate advertising), and nursing junior.

Even the term “Tupperware burp,” used to describe the expelling of air from the Tupperware container after application of the lid, seems to extend a metaphor equating women’s faculties solely with a predisposition for nurturing and domesticity.

The Tupperware corporate culture offered an alternative to the patriarchal structures of conventional sales structures, which many women, completely alienated from the conventional workplace, wholeheartedly embraced.

Despite the ingenuity of the airtight container, it was Tupperware’s appeal to sociality and the valorization of women’s domestic lives, in its objects, sales system, and corporate culture, that led to success.

A range of Tupperware-style pots for storing food, and a large basin.

Wise, a single mom, could see how great Tupperware could be to have in the household and came up with the idea of a Tupperware party.

To demonstrate Tupperware’s patented seal, Brownie Wise tosses a bowl filled with water at a party.

Brownie Wise and Earl Tupper, whose relationship ended in a flurry of lawsuits

Brownie Wise, the original “hun”.

Tupperware home party in Sarasota, Florida. 1958.

The annual Tupperware Homecoming “Jubilee”. 1955.

Tupperware advertising.

Tupperware parties became widespread in the 1950s.

A Tupperware party.

Tupperware advertising.

A Tupperware party.

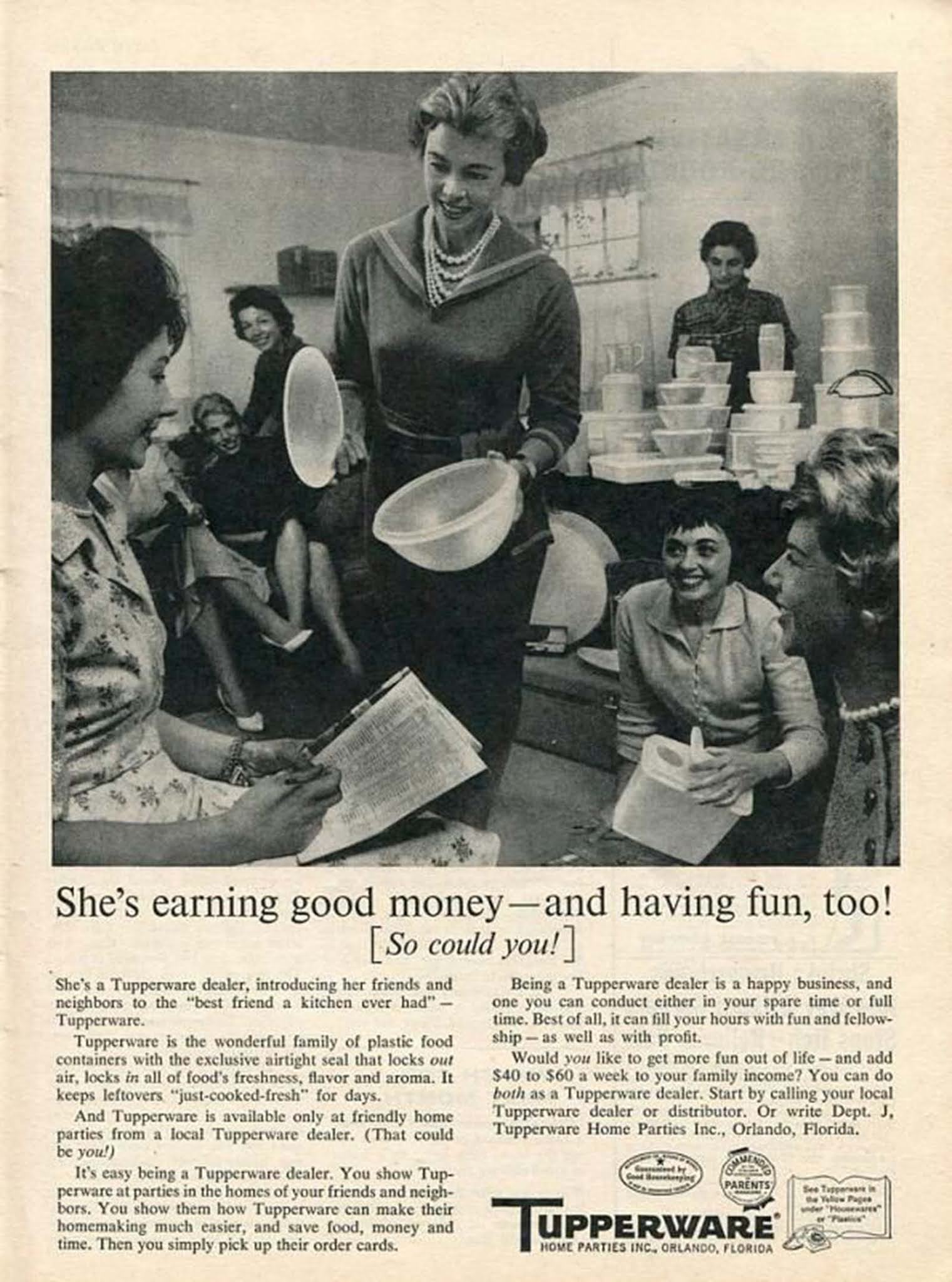

“She is earning good money and having fun, too!”, Tupperware ad.

Tupperware Parties’ in the 50s and 60s were a way of marketing the product directly to women.

(Photo credit: Archive Photos / Getty Images / Brownie Wise Papers / Archives Center / National Museum of American History / Smithsonian Institution / Article based on Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America by Alison J. Clarke).