The Seattle area was inhabited by Native Americans for at least 4,000 years before the first permanent European settlers.

The Seattle area was inhabited by Native Americans for at least 4,000 years before the first permanent European settlers.

Arthur A. Denny and his group of travelers, subsequently known as the Denny Party, arrived from Illinois via Portland, Oregon, on the schooner Exact at Alki Point on November 13, 1851.

The settlement was moved to the eastern shore of Elliott Bay in 1852 and named “Seattle” in honor of Native American Chief Si’ahl of the local Duwamish and Suquamish tribes.

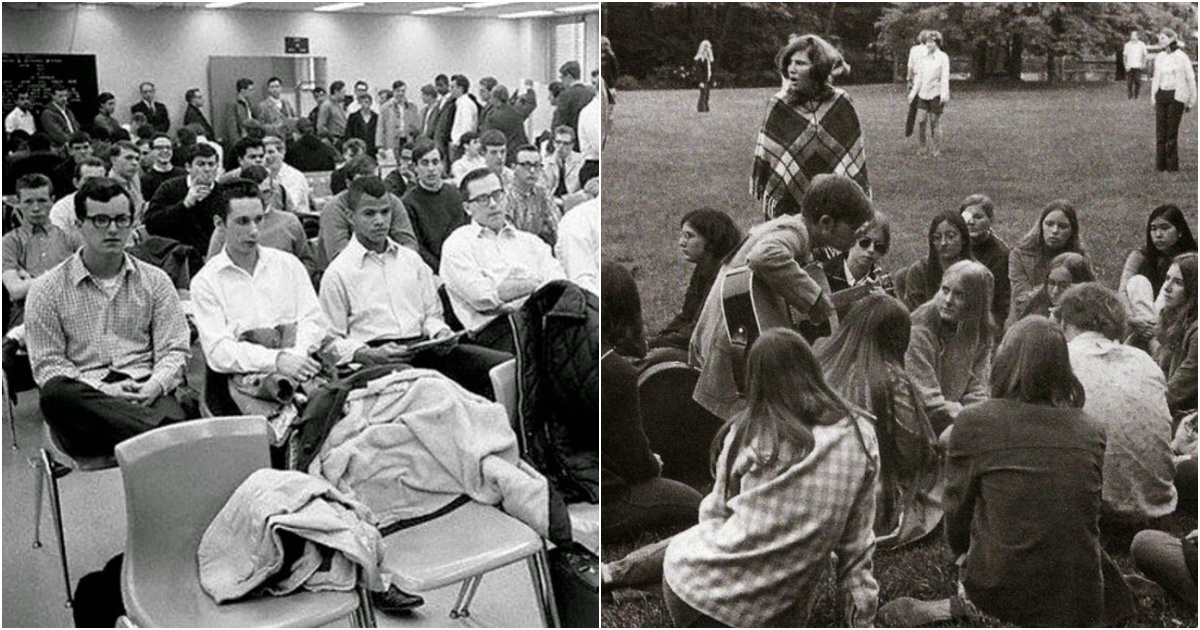

The gold rush of the 1900s led to massive immigration, with major arrivals of Japanese, Filipinos, immigrant Europeans, and European-Americans from back east. The arrival of Greeks and Sephardic Jews broadened the city’s ethnic mix.

Many of Seattle’s neighborhoods got their start around this time. At first, the city grew mainly along the water to the north and south of downtown to avoid steep grades.

However, the new rich soon developed the land on First Hill that overlooks downtown “because it was close to downtown without being a part of it, and because it occupied a commanding position.”

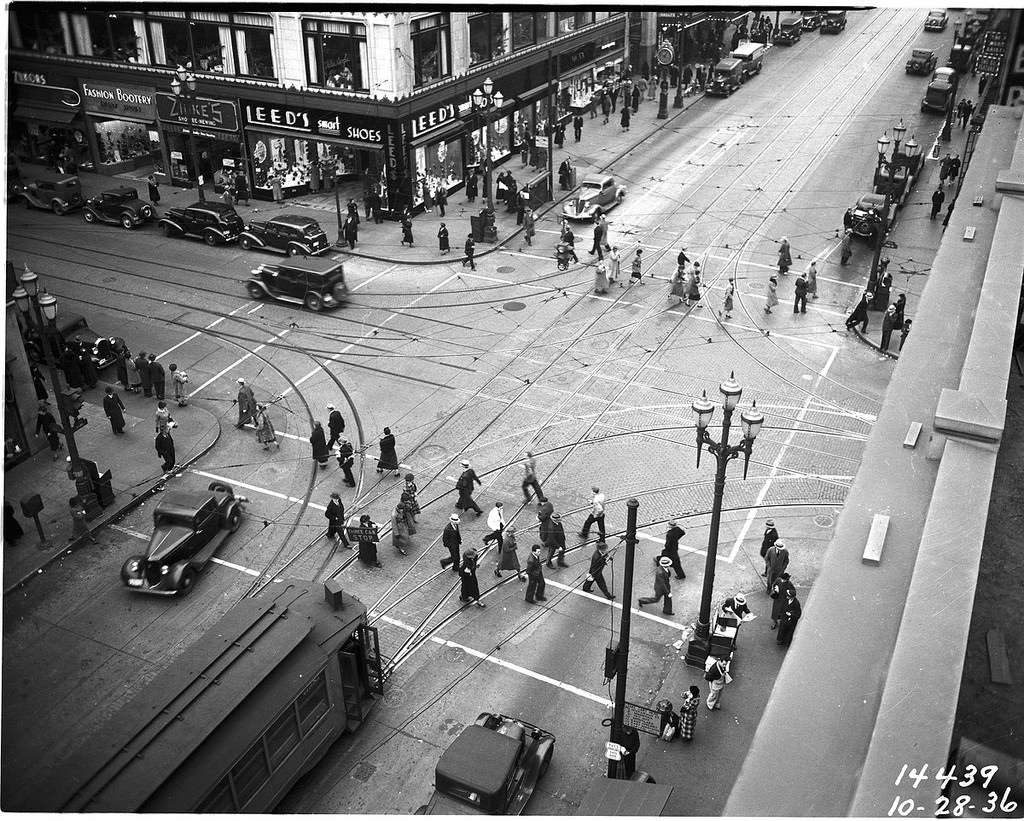

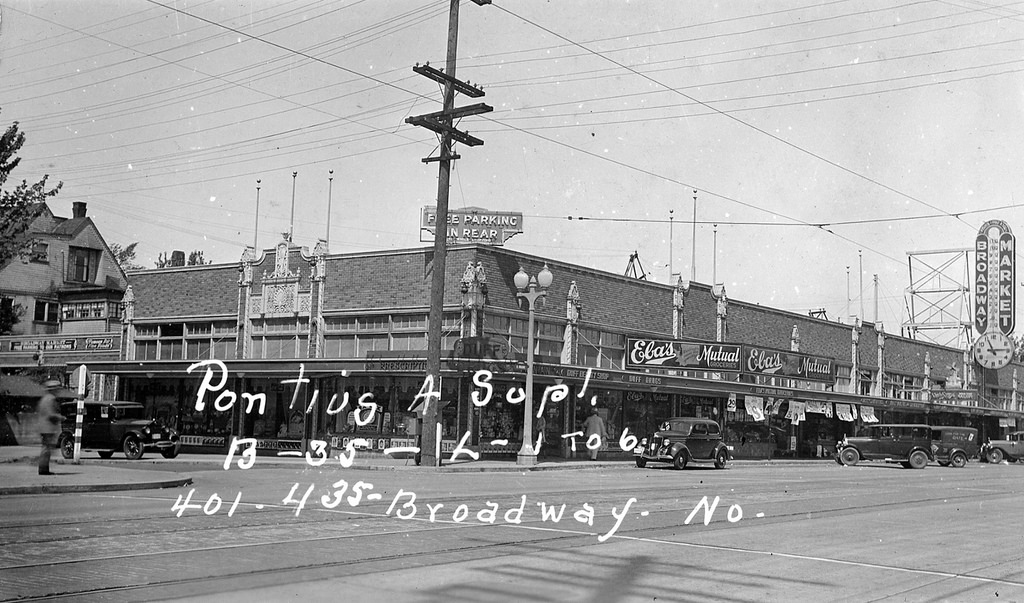

3rd and Pike, 1936.

Downtown Seattle was bustling with activity; as quickly as previous inhabitants moved out to newly created neighborhoods, new immigrants came in to take their place in the city core.

There was an enormous apartment boom in the years after 1905. A 1905 city directory lists only 19 apartment buildings. The 1911 directory has twelve columns of such listings.

Construction on the Smith Tower was completed in 1914. It was the tallest building west of the Mississippi River from its completion in 1914 until the Space Needle overtook it in 1962. It remained the tallest office building west of the Mississippi River until the Humble Building (now Exxon Building) was built in 1963.

Following the vision of city engineer R.H. Thomson, who had already played a key role in the development of municipal utilities, a massive effort was made to level the extreme hills that rose south and north of the bustling city.

From 1900 to 1914 the Denny Regrade to the north and the Jackson Regrade to the south leveled more than 120 feet (37 m) of Denny Hill and parts of First and Beacon Hills.

The Denny Regrade continued in spurts until 1930. Dirt from the Jackson Regrade filled in the swampy tidelands that are now occupied by the SoDo neighborhood as well as Safeco Field and Qwest Field.

A seawall containing dirt from the Denny Regrade created the current waterfront. More dirt from the Denny Regrade went to build the industrial Harbor Island at the mouth of the Duwamish River, south of Downtown.

Cable car at Third and Yesler, 1940.

When the First World War ended, so did Seattle’s prosperity. Economic output crashed as the government stopped buying boats, and there were no new industries to pick up the slack.

Seattle stopped being a place of explosive growth and opportunity. Western Washington was a center of radical labor agitation.

Most dramatically, a general strike occurred in 1919. The Industrial Workers of the World played a prominent role in the strike.

After surviving the general strike, Seattle mayor Ole Hanson became a prominent figure in the First Red Scare, and made an unsuccessful attempt to ride that backlash to the White House in an unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination for the presidential election of 1920.

Things picked up in the late 1920s, but then came the Great Depression. Times were rough all over the country, but Seattle was hit particularly hard because the manufacturing industries had been crowded out by the war. For example, Seattle issued 2,538 permits for housing construction in 1930, but only 361 in 1932.

8th and Olive, 1932.

Seattle saw some of the country’s harshest labor strife of the Depression. During the Maritime Strike of 1934, striking longshoremen faced off with police and strikebreakers in a series of daily skirmishes that became known as “The Battle of Smith Cove”.

As a result of the violence of the strike, Seattle lost much of its maritime traffic to the Port of Los Angeles. This was followed by the temporary ascendancy of the New Order of Cincinnatus, a “conservative and moralistic reform group” that challenged both the Democratic and Republican parties, and was widely accused of “fascist” or “proto-fascist” tendencies.

Despite this, and despite enormous police corruption, Roger Sale argues that the Seattle between the wars was a pretty nice place to live, especially to grow up in.

The city was still full of single-family wood houses and parks from the Olmstead development, but because of the crash they were affordable—at least to those who still had jobs.

Seattle between the wars, writes Sale “is what suburbs try to be, but never achieve because they cannot stand things so jammed together, all for a family whose income could be well under two thousand dollars a year.”

Seattle settled down into a kind of stasis between the wars, as growth subsided while those who lived in the city stayed.

Chief Seattle statue at Fifth and Denny, 1936.

Although no longer the economic powerhouse it had been around the start of the 20th century, it was in the 1920s that Seattle first began seriously to be an arts center.

The Frye and Henry families put on public display the collections that would become the core of the Frye Art Museum and Henry Art Gallery, respectively.

Nellie Cornish had established the Cornish School (now Cornish College of the Arts) in 1914. Australian painter Ambrose Patterson arrived in 1919; over the next few decades Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, Guy Irving Anderson, and Paul Horiuchi would establish themselves as nationally and internationally known artists.

Bandleader Vic Meyers and others kept the speakeasies jumping through the Prohibition era, and by mid-century the thriving jazz scene in the city’s Skid Road district would launch the careers of musicians including Ray Charles and Quincy Jones.

Lenora Street viaduct, Seattle, 1931.

Alaskan Way, 1939.

Lifeguard class at Green Lake, Seattle, 1936.

Alaskan Way, 1939.

Looking up Pike Street from First Avenue, 1930.

Ballard Bridge, 1941.

Newsstand at 12th & Union, Seattle, 1946.

Bell Street viaduct under construction, 1931.

Removal of streetcar tracks on Third Avenue, 1943.

Broadway and John St., Seattle, 1934.

Third Avenue looking north from Cherry Street, 1930.

Broadway line at Second & Columbia, June, 1941.

Broadway Market, Harrison and Broadway, 1937.

Broadway Safeway, Broadway at Mercer, 1937.

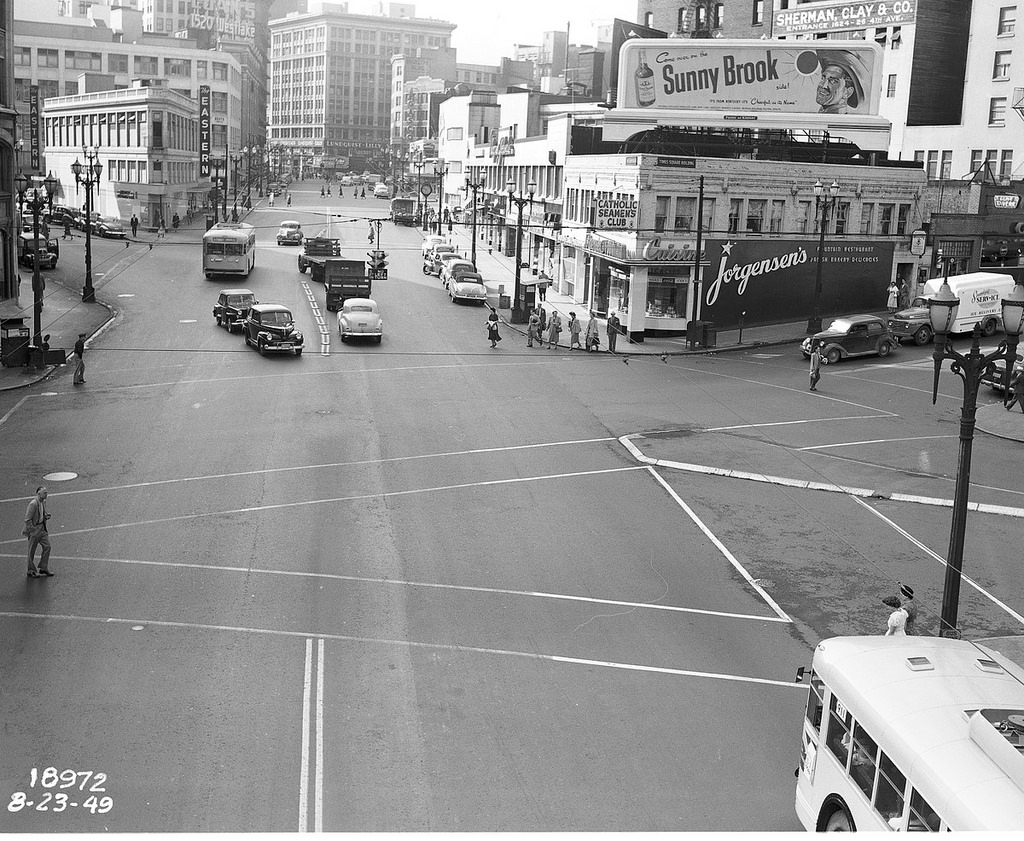

Denny Way, 1949.

Diamond District, Seattle, 1944.

Dooley’s Restaurant, 1940.

Fourth Avenue, 1937.

In front of the Frye Hotel on 3rd and Yesler, 1945.

International District, Seattle, 1945.

Lake Union and Capitol Hill, 1945.

Nickerson Street, Dexter Avenue and Westlake Avenue, 1949.

Pioneer Square, Seattle, 1945.

Queen Anne Hill and aircraft carriers, 1946.

Safety island at Westlake and Olive, 1938.

Seattle transit system line truck at Third & Pike, June 1946.

Seattle transit system twin trolley coach at Third & Marion, April 9, 1947.

Seattle transit twin trolley coach at Third & Union, March 1946.

Seattle’s waterfront, 1945.

Second and Pike, 1934.

Second Ave. south from Union St., Seattle, 1930.

Second Avenue decorated for Potlatch celebration, 1934.

Second Avenue, Seattle, 1944.

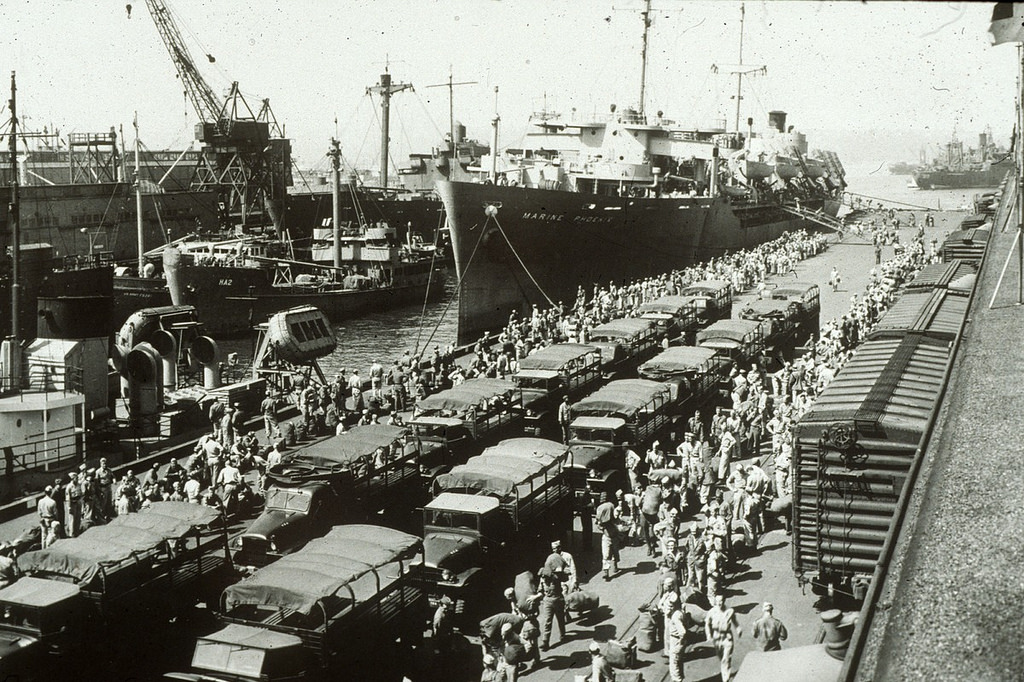

Ship loading at Pier 39, Seattle, 1946.

Snow on Capitol Hill, 1943.

SoDo, Seattle, 1945.

The Diamond District, Seattle, 1946.

The Diamond District, Seattle, 1946.

Up Yesler, Seattle, 1945.

Westlake and Olive, 1949.