The flight attendant occupation took permanent shape in the 1930s as “women’s work,” that is, work not only predominately performed by women but also defined as embodying white, middle-class ideals of femininity.

As the nascent commercial aviation industry sought to lure well-heeled travelers into the air, airline managers and stewardesses together defined the new field of in-flight passenger service around the social ideal of the “hostess.”

A stewardess’s foremost duty was to mobilize the nurturing instincts and domestic skills to serve passengers, much as middle-class, white women were expected to treat guests in their own homes.

The early airlines’ crystallizing idea of the stewardess alose demanded, however, that the hostess to be as desirable as she was nurturing. From the start, stewardess work was restricted to white, young, single, slender, and attractive women.

A 1936 New York Times article described the requirements: The girls who qualify for hostesses must be petite; weight 100 to 118 pounds; height 5 feet to 5 feet 4 inches; age 20 to 26 years. Add to that the rigid physical examination each must undergo four times every year, and you are assured of the bloom that goes with perfect health.

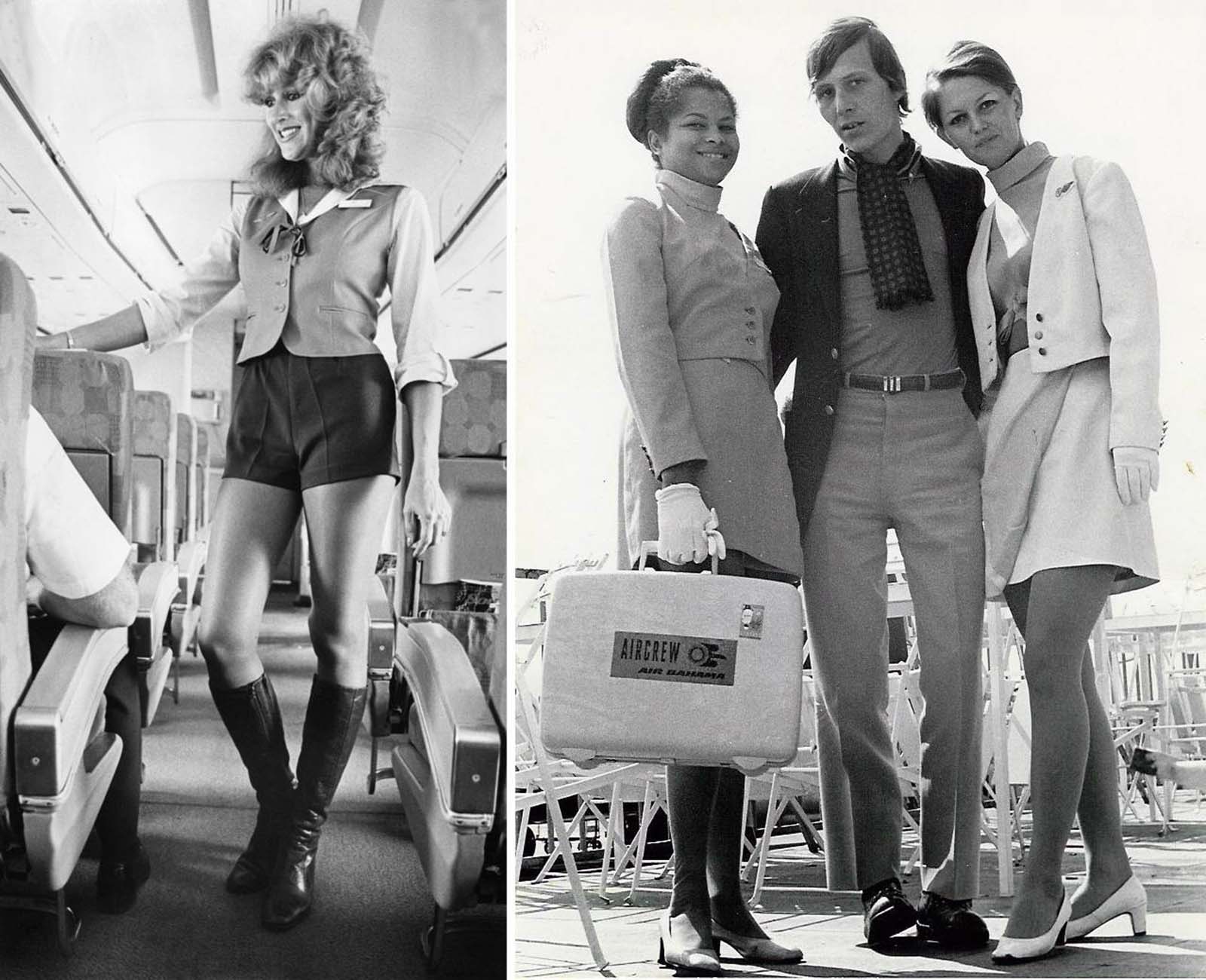

Pacific Southwest Airlines flight attendants, circa the 1970s.

The post-WWII America changed drastically and millions of Americans started to travel on airplanes and the stewardess profession expanded further.

Now, young working women did not have to change bedpans or take dictation; they could travel the world, meet important people, and lead exciting lives. The stewardess position was well paid, prestigious, and adventurous – and it quickly became the nation’s most coveted job for women.

Scores of qualified young women applied for each opening so airlines had their pic and could hire only the creme de la creme. In order to win a stewardess position, an applicant had to be young, beautiful, unmarried, well-groomed, slim, charming, intelligent, well educated, white, heterosexual, and doting.

In other words, the postwar stewardess embodied mainstream America’s, perfect woman. She became a role model for American girls, and an ambassador of feminity and the American way abroad.

A group of young French and German women discussing posture during a session of Trans World Airlines’ stewardess school in Kansas City, Missouri, 1961.

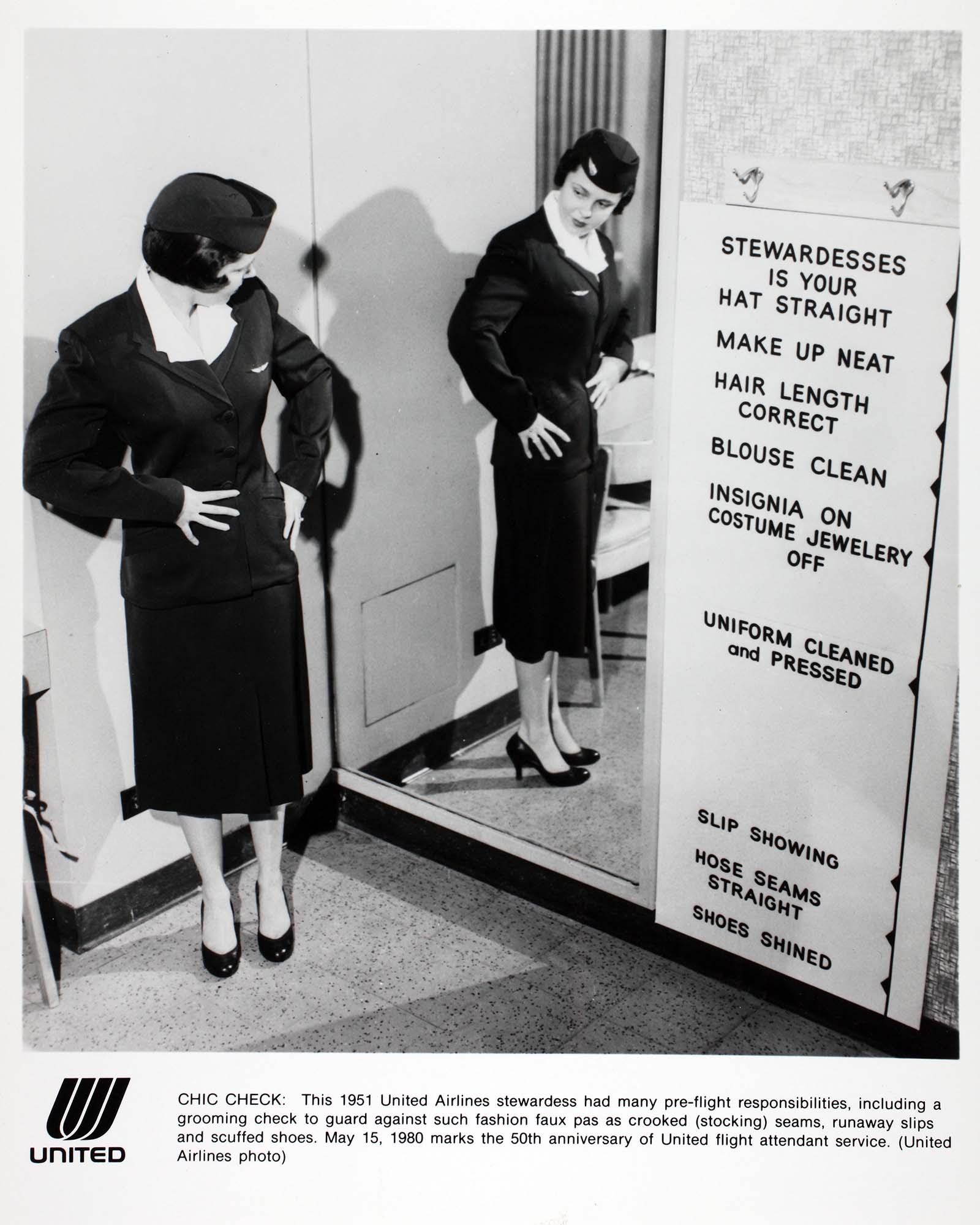

The appearance was considered as one of the most important factors to become a stewardess. At that time, airlines believed that the exploitation of female sexuality would increase their profits; thus the uniforms of female flight attendants were often formfitting, complete with white gloves and high heels.

In the United States, they were required to be unmarried and were fired if they decided to wed. A stewardess could not be pregnant. A stewardess could not grow older than her early thirties.

Because no one tried to hide the fact that flight attendants were there to be eye candy, big-named designers had a fun time dressing them up and coming up with sexy new gimmicks to promote air travel.

In 1968, Jean Louis gave United Airlines stewardesses a simple, mod A-line dress with a wide stripe down the front and around the collar, and paired it with a big, blocky kefi-type cap.

The stewardess image reached its height of sexualization, becoming a collective cultural fantasy that airlines shamelessly promoted through their advertising.

Stewardesses in training at the American Airlines college for new flight attendants in Texas, 1958.

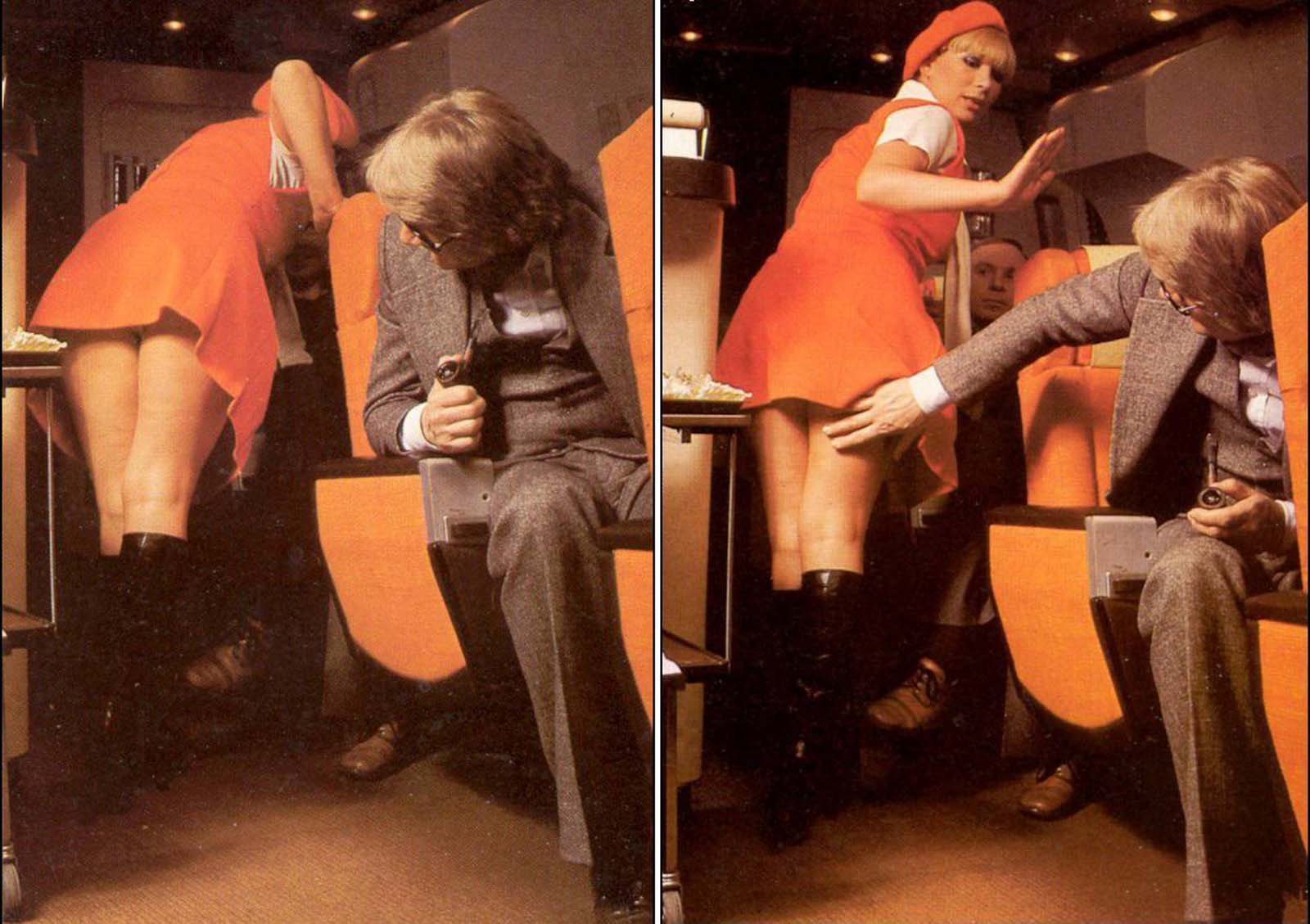

The dark side of this trope was that women who got this prestigious position were often subjected to sexual harassment from drunken passengers, who might pinch, pat, and proposition the stewardesses while they worked, according to Kathleen Barry’s Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants.

Despite their dual roles as mothering servants and objects of sexual fantasy, stewardesses were fighting for changes inside the airline industry. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s first complainants were female flight attendants complaining of age discrimination, weight requirements, and bans on marriage.

Originally female flight attendants were fired if they reached age 32 or 35 depending on the airline, were fired if they exceeded weight regulations, and were required to be single upon hiring and fired if they got married.

In 1968, the EEOC declared age restrictions on flight attendants’ employment to be illegal sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The restriction of hiring only women was lifted at all airlines in 1971. The no-marriage rule was eliminated throughout the US airline industry by the 1980s. The last such broad categorical discrimination, the weight restrictions, were relaxed in the 1990s through litigation and negotiations.

Pacific Southwest Airlines employee in mini-skirts and go-go boots.

A trio of Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) flight attendants visiting New York in 1958.

Pre-flight stewardess responsibilities for United Airlines, 1951.

National Airlines stewardess Cheryl Fioravante, subject of the 1971 “Fly Me” ad campaign, in Miami. The National Association of Women (NOW) attempted to halt the campaign claiming it was vulgar.

Portrait of an American Airlines stewardess posing in uniform on an airplane in 1967, part of an ad campaign for the airline.

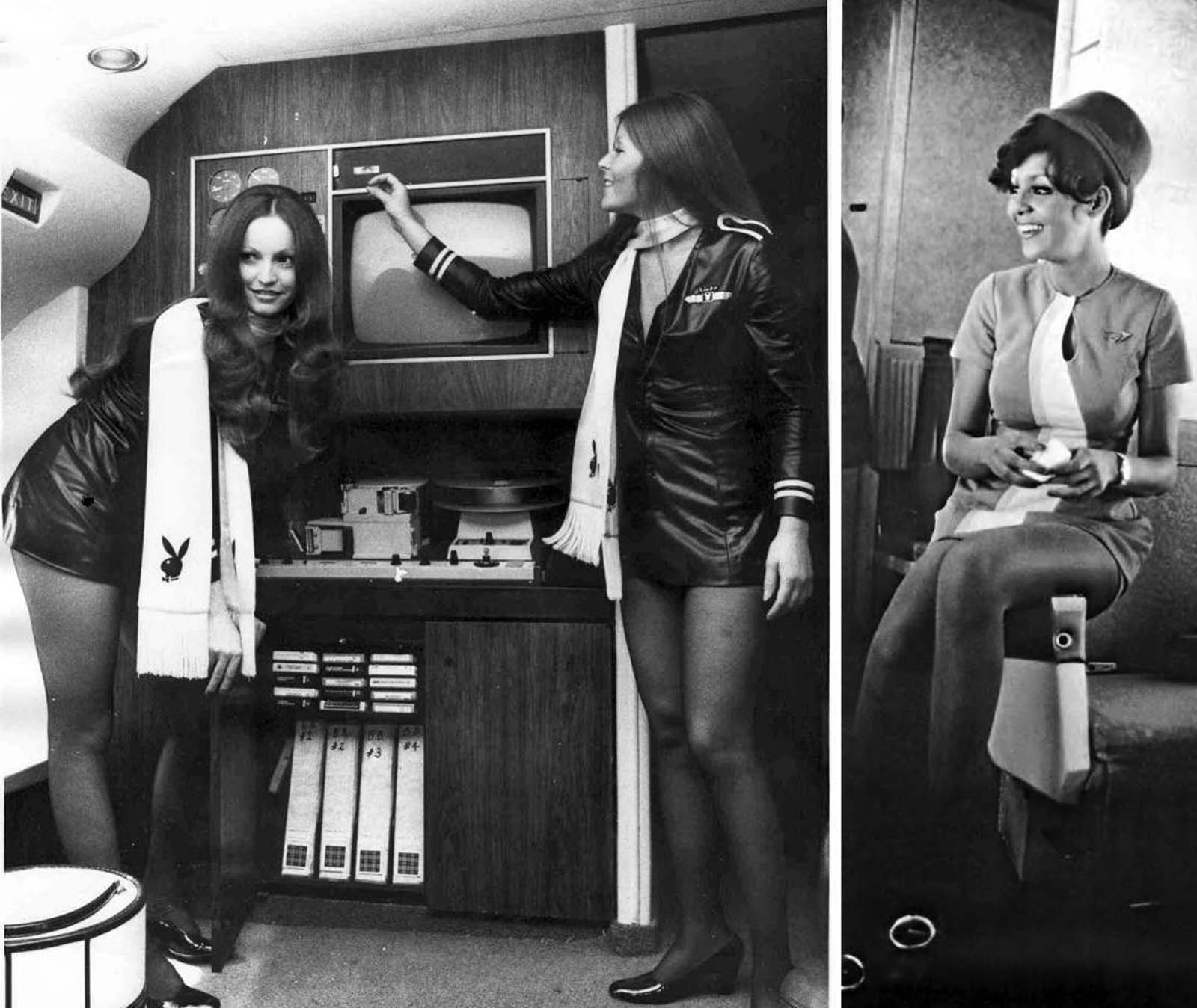

PSA flight attendants, circa the 1970s.

PSA flight attendants, circa the 1970s.

PSA flight attendants, circa the 1970s.

A stewardess speaking to men on a flight in 1958.

Flight attendant helping passengers exit a plane in 1958.

American Airlines stewardesses from a 1967 ad campaign.

Pacific Southwest Airlines advertisement, 1970s.

United Airlines stewardess with coats, circa the 1940s.

Stewardesses working for Southwest Airlines of Texas wear hot pants and leather boots in 1972. The airline’s motto was “sex sells seats,” and drinks served onboard flights had suggestive names like “Passion Punch” and “Love Potion.”

PSA flight attendants, circa the 1970s.

PSA flight attendants, circa the 1970s.

Racial diversity in the industry began mid century. Ruth Carol Taylor became first black flight attendant in 1958, after filing a complaint against Trans World Airline (TWA) for racial discrimination. Regional carrier Mohawk Airlines eventually hired her.

Beginning in the late 1960s, flight attendants became leaders in the rising feminist movement.

Photos of some of the various uniforms worn by air hostess of the National Airways Corporation (NAC) between 1959 and 1975. NAC went on to be merged with Air New Zealand.

Back in the day, “stewardesses” would start working at 18 or 20 before going off to college or getting married.

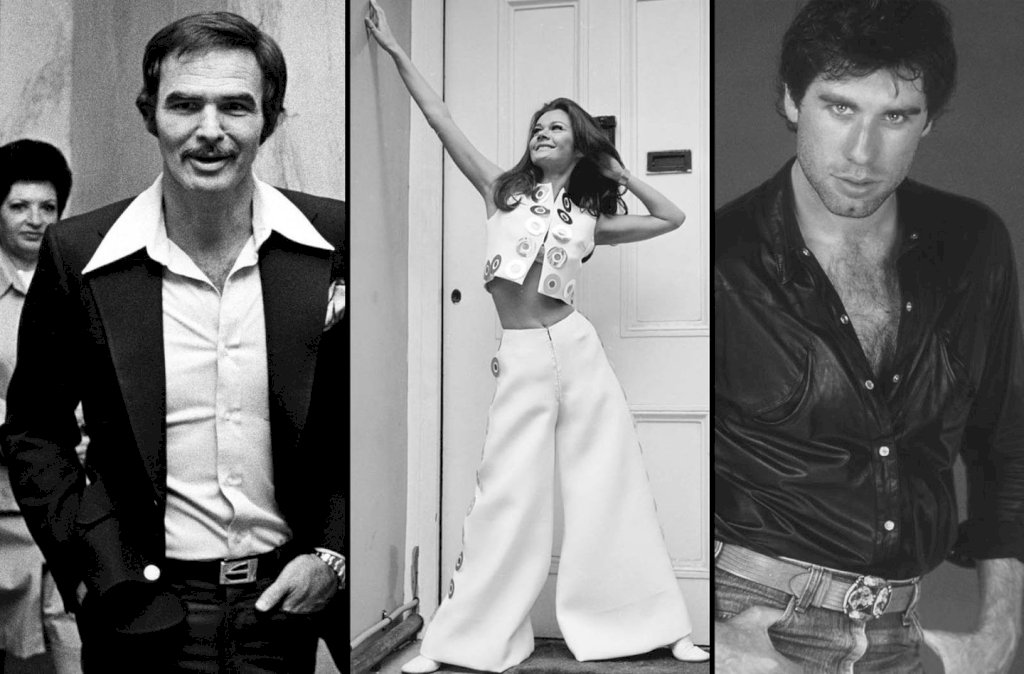

Marketing for airlines used to focus on the mostly male clientele and portrayed stewardesses as entertainment for passengers.

Every day we wear orange: A former PSA stewardess said that they were required to wear Hula Orange lipstick and had to go through inspections that ensured they shaved their legs.

Ads for flight attendant jobs during this period called for ‘girls who smile and mean it.

Stewardesses had to do weigh-ins and could be fired if they were two pounds over the airline’s expectations.

They would also be fired on the spot if they got married or pregnant and were forced to retire before age 32.

Viewing stewardesses as sex symbols is something that began in the 1930s, however, many women were still desperate to fill the roles because it allowed them the chance to travel.

Stewardesses lined up in front of an airplane.

Many stewardesses recalled that getting grabbed by male passengers was a part of the job.

Long legs were a must: Qualifications for becoming a stewardess included being a young, pretty, thin, and single woman.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that airlines began changing their treatment of stewardesses which is evident in the more professional attire they wear today.

(Photo credit: SDASM Archives / The Life Picture Collection / San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives / The Jet Sex: Airline Stewardesses and the Making of an American Icon by Victoria Vantoch / Femininity in Flight: A History of Flight Attendants by Kathleen Barry).